Retail spaces are designed for impulse shopping. When you go to a store looking for socks and come out with a new shirt, it’s only partly your fault. Shops are trying to look so beautiful, so welcoming, the items so enticingly displayed and in such vast quantity, that the consumer will start buying compulsively.

This is the Gruen Effect.

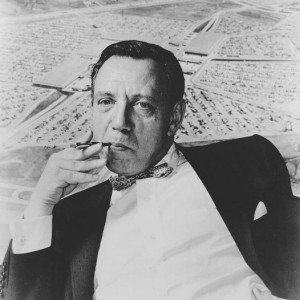

The Gruen effect is named after Victor Gruen, born in Vienna in 1904 to a Jewish family. Gruen, born Viktor Grünbaum, left Austria in 1938 for New York City, where he made a name for himself designing shops and retail spaces. This was a particular challenge during the lean years of the late 30s.

People had no money. They just wouldn’t go into shops.

However, Gruen figured out how to lure customers inside with amazingly appealing window displays

Gruen argued that good design equaled good profits. The more beautiful the displays and surroundings, the longer consumers are will want to stay in a shop. The more time shoppers spend in a store, the more they will spend.

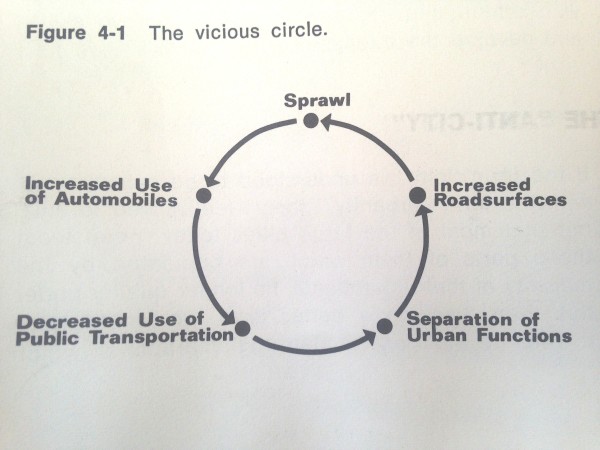

Gruen started making storefronts all over the country. And in his travels across the United States, Gruen saw how much time Americans spent riding around in their cars, cut off from the city and from each other. This was especially true in the suburbs.

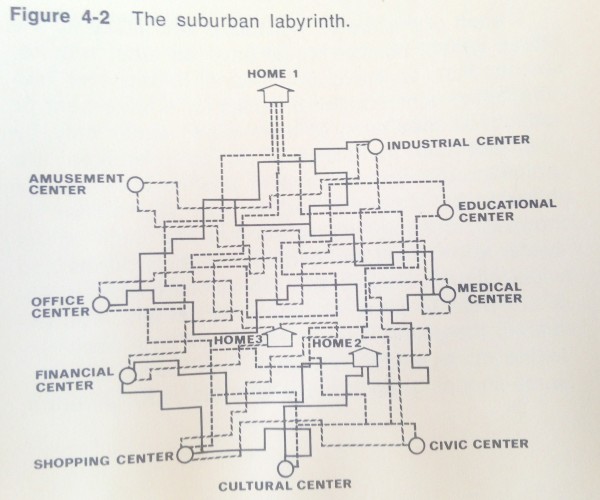

The suburbs lacked what sociologist Ray Oldenburg calls third places. If home is the primary place, and work is a second place, then a third place anywhere else one goes to be around other people—to build community, to hang out, to feel connected. Gruen wanted to give the American suburbs that third place.

Victor Gruen imagined designing an environment full of greenery and shops. An indoor plaza which could be an island of connection in the middle of the sprawl. One that would get people out of their cars in order to walk and stroll within them.

Gruen saw his structure as an architectural panacea—it would remedy environmental, commercial, and sociological problems with the creation of a single building.

Gruen presented his solution for America: The Shopping Mall.

Gruen’s full vision for the mall was more than just shops. He imagined them as mixed-use facilities, with apartments, offices, medical centers, child-care facilities, libraries, and (since it was the 1950s) bomb shelters.

Gruen wrote theoretical sketches of shopping malls long before he ever built one, but for a long time, none of his ideas came to fruition. Then in 1952, the owner Dayton Company commissioned him to build the very first indoor, climate-controlled shopping center. It would be in Edina, Minnesota.

Southdale Center opened in 1956, and what Gruen emphasized (and what the media would celebrate) was the massive center court, covered in a skylight, which was supposed to mimic a town square. Gruen’s subsequent malls were all mostly based off this original Edina design, and the center court became a hallmark of shopping mall architecture.

Southdale Center wasn’t quite mixed-use like Gruen imagined. People didn’t live there, and there were no daycare centers or post office. But Southdale did have local shops of all kinds. And plenty of shoppers.

From the outside, Southdale Center is not much to look at. It looks like a mall: an ominous, amorphous, boxy shape. In designing the shopping malls, Gruen ended his razzle-dazzle storefronts and window displays. Southdale hardly has exterior windows at all. The draw now is what’s inside the mall: Gruen wants his shopping centers to have blank facades, with no signage on them, that consumers would then enter and be dazzled by the interiors.

Malls are suburban pilgrimage sites, which, of course, Americans had to drive to. Gruen knew that Americans loved to drive. So the mall was his compromise: shoppers had to walk once inside, but they could drive over.

For better or for worse, Gruen was right. Americans loved driving to his malls. He got commissions for them all over the country

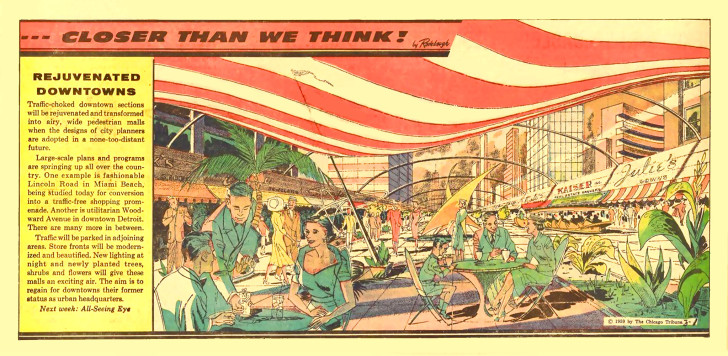

Over time, Gruen saw that in erecting these malls, he was draining life from the actual cities. So for a time, Gruen got involved in urban renewal projects, drawing directly on some of the lessons learned in his suburban shopping malls and applying them to struggling downtown.

Gruen turned city centers into pedestrian-only spaces full of public art and greenery and lined with shops. He made plans for Boulder, Fresno, Ft. Worth, and Kalamazoo. The Kalamazoo plan became the first outdoor pedestrian shopping mall in the United States.

Gruen even had a concept for a pedestrian mall in New York, and actually got Manhattan to close down 5th avenue for a couple weeks, as a test.

A city’s downtown, however, is not a mall. It’s not so easily “fixed” and controlled. American cities weren’t going to become the pleasant, sterile shopping environments Gruen wanted.

In 1968, Gruen moved from L.A. back to Vienna, back to the greenery and plazas he had been trying to imitate. But he could not escape his own creation. A shopping mall was being built on the edge of town.

In Gruen’s mind, Vienna was already perfect; it didn’t need a mall the way the broken American suburbs did. As he saw it, his original vision had been totally skewed.

About ten years after his return to Vienna, Gruen gave a speech in which he declared, “I refuse to pay alimony for these bastard developments.”

Victor Gruen, the mall maker, became the foremost mall critic.

Meanwhile, America’s love affair with malls continued, for a time. From the 1960s to about the 1990s, it was cool to go to the mall. Literally—it might have been the only air-conditioned place in town.

Before we all lived and worked in air-conditioned, climate-controlled environments, the mall was a special escape from the heat and the cold. Now, after days spent indoors, shoppers want to go outside, and popular tastes have veered away from the indoor mall.

Mall construction peaked in 1990, and the last brand new standard conventional mall in the U.S. was built in 2006. A new product has entered the scene. A kind of shopping center that the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC) calls a “Lifestyle Center.”

Lifestyle centers started appearing in the 90s. They are malls disguised as a main street, with no roof and a lot more boutiques and restaurants. Even though they’re full of chain stores, “Lifestyle Centers” are still sunny and walkable and bustling. They are kind of what Victor Gruen imagined.

As for those old climate-controlled, fully enclosed shopping malls—some have fallen into disrepair. Others have actually been repurposed. Several shopping malls have been retrofitted into Latino community centers, like Plaza Fiesta outside of Atlanta.

At Plaza Fiesta, a lot of stores have been cut up into much smaller mom and pop shops selling Western wear and quinceañera dresses, and Plaza Fiesta also has a steady events calendar of performances. These sort of community malls have finally become true third places, where people can gather and spend money. All in the shell of the failed design.

Many people—architectural historians especially—think Gruen was a horrible architect. Yes, the exteriors of his shopping centers are uniformly boring, but for Gruen, the exteriors weren’t the point. It was the life and the atmosphere within the mall. Those fountains, the cheesy statues, the elevator music piped in through all those speakers—those are all part of the Gruen Effect, and they helped turn shopping malls into spaces where we felt comfortable staying and spending time and money.