The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is is not what you think it is.

Review of Justin E.H. Smith, The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is: A History, A Philosophy, A Warning (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022).

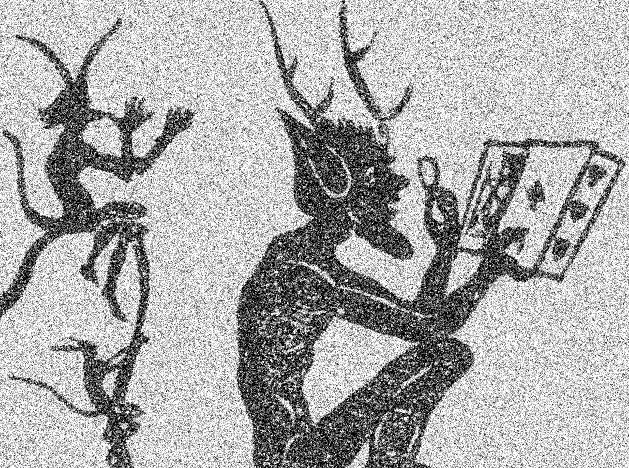

According to one theory, the internet is made of demons. Like most theories about the internet, this one is mostly circulated online. On Instagram, I saw a screenshot of a Reddit post, containing a screenshot of a 4chan post, containing a screenshot of Tweet, containing two images. On the left, the weird, loopy lines of a microprocessor. On the right, the weird, loopy lines of a set of Solomonic sigils. Caption: ‘Boy I love trapping demons in microscopic silicon megastructures to do my bidding, I sure hope nothing goes wrong.’ In other versions, the demons themselves are the ones who invented the internet; it’s just their latest move in a five-thousand-year battle against humanity. As one four-panel meme comic explains:

The king’s pact binds them. They cannot show themselves or speak to us.

1) Create ways to see without seeing

2) Create ways to speak without speaking

Pictures of more Solomonic sigils, progressing into laptops and iPhones. The fourth panel, the punchline, has no words. Only a giant, mute, glassy-eyed face.

This theory is—probably—a joke. It is not a serious analysis. But still, there’s something there; there are ways in which the internet really does seem to work like a possessing demon. We tend to think that the internet is a communications network we use to speak to one another—but in a sense, we’re not doing anything of the sort. Instead, we are the ones being spoken through. Teens on TikTok all talk in the exact same tone, identical singsong smugness. Millennials on Twitter use the same shrinking vocabulary. My guy! Having a normal one! Even when you actually meet them in the sunlit world, they’ll say valid or based, or say y’all despite being British. Memes on Instagram have started addressing people as my brother in Christ, so now people are saying that too. Clearly, that name has lost its power to scatter demons.

Everything you say online is subject to an instant system of rewards. Every platform comes with metrics; you can precisely quantify how well-received your thoughts are by how many likes or shares or retweets they receive. For almost everyone, the game is difficult to resist: they end up trying to say the things that the machine will like. For all the panic over online censorship, this stuff is far more destructive. You have no free speech—not because someone might ban your account, but because there’s a vast incentive structure in place that constantly channels your speech in certain directions. And unlike overt censorship, it’s not a policy that could ever be changed, but a pure function of the connectivity of the internet itself. This might be why so much writing that comes out of the internet is so unbearably dull, cycling between outrage and mockery, begging for clicks, speaking the machine back into its own bowels.

This incentive system can lead to very vicious results. A few years ago, a friend realized that if she were murdered—if some obsessed loner shot her dead in the street—then there were hundreds of people who would celebrate. She’d seen similar things happen enough times. They would spend a day competing to make exultant jokes about her death, and then they would all move on to something else. My friend was not a particularly famous or controversial person: she had some followers and some bylines, but probably her most divisive article had been about tax policy. But she was just famous enough for hundreds of people, who she didn’t know and had never met, to hate her and want to see her dead. It wasn’t even that they had different political opinions: plenty of these people were on the same side. They would laugh at her death in the name of their shared commitment to justice and liberation and a better future for all.

Maybe these were simply bad people, but I’m not so sure. There’s an incident I think about a lot: back in 2019, a group of bestselling authors in their 40s and 50s decided to attack a young college student online for the crime of not liking their books. Apparently wanting to read anything other than YA fiction means that you’re an agent of the patriarchy. The student was, of course, a woman. So what? Punish her! For a while they whipped up thousands of people in sadistic outrage. Even her university joined in. But then, the tide suddenly shifted, and one by one they were forced to apologize. ‘I absolutely messed up. I will definitely do better and be more mindful moving forward. I made a mistake.’ Of course, these apologies weren’t enough. The discourse was unanimous: we want you to grovel more; we want to see you suffer. Was absolutely everyone involved making the same personal moral lapse? Or could it be that they’d all plugged their consciousnesses into a planet-sized sigil that summons demons?

Back when I spent half my days on social media, I did much the same thing. I would probably have also celebrated a murder, if the victim had once tweeted something I didn’t like. Now, looking back on those days is like trying to remember the previous night through a terrible hangover. Oh god—what have I done? Why did I keep saying things I didn’t actually believe? Why did I keep behaving in ways that were clearly cruel and wrong? And how did I manage to convince myself that all of this was somehow in the service of the good? I was drunk on something. I wasn’t entirely in control.

Ways to speak without speaking. If the internet makes people tangibly worse—and it does—it might be because it lives in a strange new middle ground between writing and speech. Like speech, social media messages seem to belong to a now: briefly suspended in an instant, measurable down to the second. But like writing, there’s a permanent archive you can choose to dig up later. Like speech, social media is dialogic and responsive; you can carry out an instantaneous back-and-forth, as if the other person is right in front of you. But like writing, with social media the other person is simply not there. And instead of a book or a letter or a shopping list—a trace, a thing the other person has made—you’re looking at a screen, this cold bundle of pixels and wires. This blank and empty object, which suddenly starts talking to you like a human being.

The internet is not a communications system. Instead of delivering messages between people, it simulates the experience of being among people, in a way that books or shopping lists or even the telephone do not. And there are things that a simulation will always fail to capture. In the philosophy of Emmanuel Lévinas, your ethical responsibility to other people emerges out of their face, the experience of looking directly into the face of another living subject. “The face is what prohibits us from killing.” Elsewhere: “The human face is the conduit for the word of God.” But Facebook is a world without faces. Only images of faces; selfies, avatars: dead things. Or the moving image in a FaceTime chat: a haunted puppet. There is always something in the way. You are not talking to a person: the machine is talking, through you, to itself.

As more and more of your social life takes place online, you’re training yourself to believe that other people are not really people, and you have no duty towards them whatsoever. These effects don’t vanish once you look away from the screen. The internet is not a separate sphere, closed off from ordinary reality; it structures everything about the way we live. Stories of young children trying to swipe at photographs or windows: they expect everything to work like a phone, which is infinitely responsive to touch, even if it’s impossible to engage with on any deeper level. Similarly, many of the big conflicts within institutions in the last few years seem to be rooted in the expectation that the world should work like the internet. If you don’t like a person, you should be able to block them: simply push a button, and have them disappear forever.

In 2011, a meta-analysis found that among young people the capacity for empathy (defined as Empathic Concern, “other-oriented feelings of sympathy,” and Perspective-Taking, the ability to “imagine other people’s points of view”) had massively declined since the turn of the millennium. The authors directly associate this with the spread of social media. In the decade since, it’s probably vanished even faster, even though everyone on the internet keeps talking about empathy. We are becoming less and less capable of actual intersubjective communication; more unhappy; more alone. Every year, surveys find that people have fewer and fewer friends; among millennials, 22% say they have none at all. For the first time in history, we can simply do without each other entirely. The machine supplies an approximation of everything you need for a bare biological existence: strangers come to deliver your food; AI chatbots deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy; social media simulates people to love and people to hate; and hidden inside the microcircuitry, the demons swarm.

I don’t think this internet of demons is only a metaphor, or a rhetorical trick. Go back to those sigils, the patterns of weird loopy goetic lines that signify the presence of demons in online memes. Most of those designs come from the grimoires of the sixteenth and seventeenth century—and of these, probably the most significant is the Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonis, or the Lesser Key of Solomon. Unlike most old books of demonology, the Lesser Key is still in print, mostly because it was republished (and extensively tinkered with) by Aleister Crowley. But despite its influence, the Lesser Key is mostly plagiarized: entire sections were simply ripped out of other books circulating at the time. Most prominently, it reproduces much of the Steganographia, a book of magic written by Johannes Trithemius, a Benedictine abbot and polymath, around 1499.

The Steganographia is a blueprint for the internet. Most of the book is taken up with spells and incantations with which you can summon aerial spirits, who are “infinite beyond number” and teem in every corner of the world. Here, the purpose of these spirits is to deliver messages—or, more properly, to deliver something that is more than a message. Say you want to convey some secret information to someone: you compose an innocuous letter, but before writing you face the East and read out a spell, like this one to summon the spirit Pamersyel: “Lamarton anoyr bulon madriel traſchon ebraſothea panthenon nabrulges Camery itrasbier rubanthy nadres Calmoſi ormenulan, ytules demy rabion hamorphyn.” Immediately, a spirit will become visible. Then, once the other person receives the letter, they speak a similar spell, and “having said these things he will soon understand your mind completely.” A kind of magic writing that works like speech, instant and immediate. Not an object composed by another person, but a direct simulation of their thoughts—and one that’s delivered by an invisible, intangible network, covering every inch of the world.

Trithemius was a pious man; in a long passage at the start of the book, he insists that these spirits are not demons, and that “everything is done in accordance with God in good conscience and without injury to the Christian faith.” But readers had their suspicions; he does repeatedly warn that the spirits might harm you if given the chance. And while his internet can be used for godly ends, it can also be used for evil. “For though this knowledge is good in and of itself and quite useful to the State, nevertheless if it reached the attention of twisted men (God forbid), over time the whole order of the State would become disturbed, and not in a small way.” Today, a broad range of sensible types are worried—and not without cause—that the internet is incompatible with a civic democracy. Trithemius saw it first.

But the Seganographia held a secret, and its real purpose wasn’t revealed until a century after its publication: this book of magic is actually a book of cryptography. Not magic spells and flying demons, but mathematics. Take the spell above: if you read only the alternating letters in every other word, it yields nym di ersten bugstaben de omny uerbo, a mishmash of Latin and German meaning “take the first letter of every word.” This is a fairly simple approach; Trithemius warns that Pamersyel is “insolent and untrustworthy,” and that the spirits under his command “speed about and by filling the air with their shouts they often reveal the sender’s secrets to everyone around.” Others are subtler. The book’s third volume wasn’t decoded until 1998, by a researcher at AT&T Labs.

There is a direct line from this fifteenth-century monk to our digital present. Pamersyel and the other spirits are algorithms, early examples of the mathematical operations that increasingly govern our lives. They are also the distant ancestors of machines like the Nazi Enigma device, a cipher so powerful that to break its code, it was necessary to build the first electronic computer. Trithemius invented the internet in a flight of mystical fancy to cover up what he was really doing, which was inventing the internet. Demons disguise themselves as technology, technology disguises itself as demons; both end up being one and the same thing.

Exactly how long have we been living with the internet? There’s a boring answer, which gives a start date some time in the second half of the twentieth century and involves “packet-switching networks.” But the more interesting answer is one that considers the meaning of the internet, rather than its technological substrate: the thought of a world lived at a distance, a dream and a nightmare that has been with us for a very long time. The internet dates back five thousand years, or five billion, or it hasn’t been invented yet. In The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is, Justin E.H. Smith pleads for the interesting answer. The internet is very old; it is “only the most recent permutation in a complex of behaviors that is as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.”

Smith is a philosopher of science at the University of Paris, an occasional Damage contributor, and one of the most interesting public intellectuals of our age. He’s one of the few people writing on the internet who manages to avoid writing like the internet. Online writing might be about birds or Proust or the Kuiper Belt, but always in a way that’s optimized for the endless, tedious war being fought on social media. Occasionally, Smith will even write about cancel culture or wokeness or Trump, but always in a way that points away from the squabbles of the day, and towards a more genuine fascination with the things and the history of the world.

In this book, he shows us prototypes for the internet in some unexpected places. Like me, Smith finds demons at the origin of the digital age: here, it’s in the Brazen Head, a magical contraption supposedly built by the thirteenth-century scholar Roger Bacon. Like a “medieval Siri,” this head could answer any yes or no question it was given; it was a thing with a mind, but without a soul. Bacon’s contemporaries were convinced that the head was real, and that he had created it with the help of the Devil. Seven hundred years ago, we were already worried about the possibility of an artificial general intelligence.

If it’s possible to build a machine that has a mind, or at least acts in a mind-like way, what does that say about our own minds? Leibniz, a pioneer of early AI, insisted that his gear-driven mechanical calculator did not think, because the purely rational and technical operations of the mind—adding, subtracting—are not real thought. “It is unworthy of excellent men to lose hours like slaves in the labor of calculation;” a calculating machine would allow us to spend more time fully inhabiting our own minds. Today, of course, it’s gone the other way: computerized systems form our opinions for us and decide what music we enjoy; dating-app algorithms choose our sexual partners. Meanwhile, the pressures of capitalism force us to act as rational agents, always calculating our individual interests, condemned to live like machines. It has all, Smith admits, gone very badly wrong. But it could have gone otherwise.

After all, there have already been many different versions of the internet; go back far enough, and the internet is simply part of nature. An elephant’s stomping foot, the clicking of a sperm whale, the chemical signals released into the air by sagebrush, all of which send meaningful messages over a long distance. “Throughout the living world, telecommunication is more likely the norm than the exception.” Mystics understood this; they have always assumed that something like the internet already existed, in their vision of a “system of hidden filaments or threads that bind all things.” Ancient philosophers, from the Stoics to the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, saw creation as a kind of cosmic textile. “How intertwined in the fabric is the thread and how closely woven the web.” Maybe, Smith suggests, it is not a coincidence that the first fully programmable computer was the Jacquard loom, a machine for entangling threads. Our digital computer network is just the latest iteration of something that permeates the entire world. The internet is happening wherever birds sing in the morning; the internet is furiously coursing through the soil beneath a small patch of grass.

It’s a fascinating argument, and a tempting one. Like Smith, I’m fascinated by very early computers, which are ultimately far more interesting than the machine I’m using to write this review. The Jacquard loom, the Leibniz machine, the Babbage engine: these devices seem to point the way to an alternative internet, something very different to the one we actually have. At one point Smith mentions Ramon Llull, a hero of mine and a major influence on Leibniz’s first doctoral dissertation, who invented a mechanical computer made of paper which he imagined could help us understand the nature of God. What would our internet look like if it had kept to its thirteenth-century purpose? Well, Smith suggests, maybe it would look like Wikipedia, “this cosmic window I am perched up against, this microcosmic sliver of all things.”

The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is is, well, not what you think it is. Some online reviewers have been surprised by this book: they expected a pointed screed about how the internet is ruining everything, and instead they get an erudite, quodlibetical adventure through the philosophy of computation. They wanted to be told that the internet is a sudden, cataclysmic break from the world we knew, and they get a “perennialist genealogy,” an account of how things are “more or less stable across the ages.” It’s not as if Smith has failed to properly consider the opposite position. The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is grew out of an essay in The Point magazine, titled “It’s All Over,” which was also about the internet but struck a very, very different tone. “It has come to seem to me recently that this present moment must be to language something like what the Industrial Revolution was to textiles.” The piece was, he writes, “the closest thing to a viral hit I’ve ever produced.” Strangely, one of the things the internet likes is essays about how awful and unprecedented the internet really is. Online essays feed off rupture. Maybe the sustained intellectual activity that comes with writing a book reveals the connections instead: the way things all seem to hang together in an invisible net. Theodor Adorno describes thought as a kind of hypertext, a network, a web:

Properly written texts are like spiders’ webs: tight, concentric, transparent, well-spun and firm. They draw into themselves all the creatures of the air. Metaphors flitting hastily through them become their nourishing prey. Subject matter comes winging towards them. The soundness of a conception can be judged by whether it causes one quotation to summon another. Where thought has opened up one cell of reality, it should, without violence by the subject, penetrate the next. It proves its relation to the object as soon as other objects crystallize around it. In the light that it casts on its chosen substance, others begin to glow.

So when I say I can’t entirely agree with the book’s thesis, this might be the internet itself speaking through me—but still, I can’t entirely agree. I still think that the internet is a serious break from what we had before. And as nice as Wikipedia is, as nice as it is to be able to walk around foreign cities on Google Maps or read early modern grimoires without a library card, I still think the internet is a poison.

This doesn’t mean that the boring answer was the right one all along. Thinkers of the past have plenty to teach us about the internet, and the world has indeed been doing vaguely internetty things for a very long time. But as I suggested above, our digital internet marks a significant transformation in those processes: it’s the point at which our communications media cease to mediate. Instead of talking to each other, we start talking to the machine. If there are intimations of the internet running throughout history, it might be because it’s a nightmare that has haunted all societies. People have always been aware of the internet: once, it was the loneliness lurking around the edge of the camp, the terrible possibility of a system of signs that doesn’t link people together, but wrenches them apart instead. In the end, what I can’t get away from are the demons. Whenever people imagined the internet, demons were always there.

Lludd and Llefelys, one of the medieval Welsh tales collected in the Mabinogion, is a vision of the internet. In fact, it describes the internet twice. Here, a terrible plague has settled on Britain: the arrival of the Coraniaid, an invincible supernatural enemy. What makes the Coraniaid so dangerous is their incredibly sharp hearing. They can hear everything that’s said, everywhere on the island, even a whisper hundreds of miles away. They already know the details of every plot against them. People have stopped talking; it’s the only way to stay safe. To defeat them, the brothers Lludd and Llefelys start speaking to each other through a brass horn, which protects their words. Today, we’d call it encryption. But this horn contains a demon; whatever you speak into it, the words that come out are always cruel and hostile. This medium turns the brothers against each other; it’s a communications device that makes them more alone. In the story, the brothers get rid of the demon by washing out the horn with wine. I’m not so sure we can do that today: the horn and its demon are one and the same thing.

■

Sam Kriss is a writer and dilettante surviving in London.