Blame it on the LSD

In the quixotic quest for the self, few have gone as far (or far out) as neurophysiologist Dr. John C. Lilly (1915–2001). “I have explored,” he wrote in 1977, “and have voluntarily entered into domains forbidden by a large fraction of those in our culture who are not curious, are not explorative and are not mentally equipped to enter these domains.”

Today, his excesses receive as much attention as his achievements. He invented the world’s first sensory deprivation tank, but almost drowned in it while high on psychedelics. He also pioneered the field of dolphin communication, helping enact the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. But his lab’s unorthodox experiments — like jerking off dolphins to completion and injecting them with LSD — ultimately discredited the field for decades.

After a promising start to a career that saw him make contributions to the fields of biophysics, neurophysiology, electronics, computer science, and neuroanatomy, Lilly was by the 1970s on science’s radical fringe, unable to secure government grants or publish in academic journals. He spent his days in his deprivation tank high on ketamine, allegedly communicating with aliens.

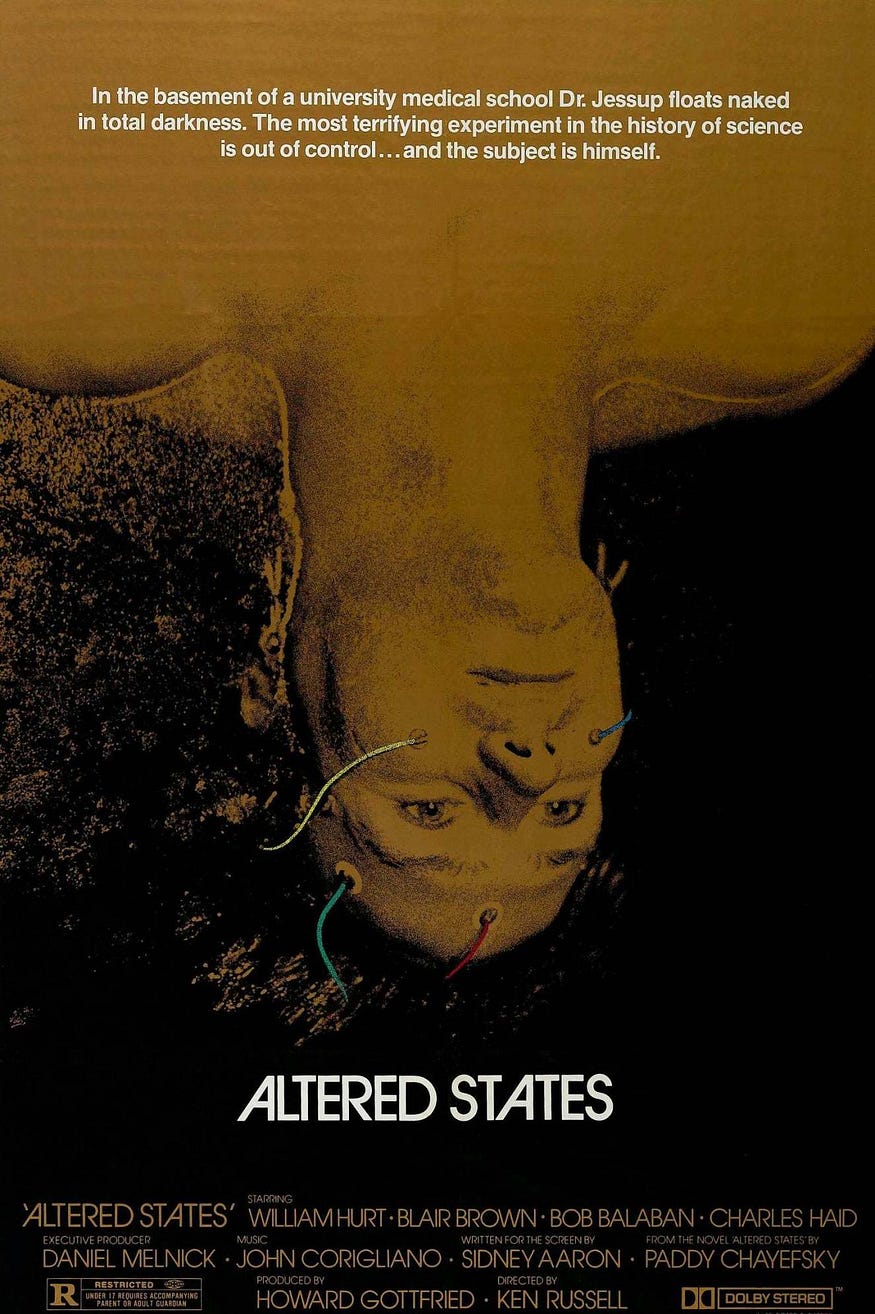

His life inspired the movie Altered States (1980), where the scientist Eddie Jessup (played by William Hurt in his film debut) combines psychedelics with sensory deprivation to horrific effect. After his colleague Mason Parrish calls him a whacko, Jessup goes on a rant that epitomized Lilly’s modus operandi throughout his career:

EDDIE JESSUP: What’s whacko about it, Mason? I’m a man in search of his true self…I think that that true self, that original self, that first self is a real, mensurate, quantifiable thing, tangible and incarnate. And I’m going to find the fucker.

John C. Lilly’s quest began in 1928 with a question: “How can the mind study itself?” He was 16, writing a prep school essay he titled “Reality.” In it, he puzzled through the relationship between thoughts, brain activity, and brain structure for the first time. The essay “laid out the trip for the rest of my life,” he recalled.

Lilly studied biology and physics at the California Institute of Technology, graduating in 1938. He went on to earn his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1942. At the height of World War II, he invented instruments for measuring gas pressure for jet pilots. But he tested the instruments on himself first—the start of a lifelong habit of self-experimentation that would earn Lilly the ire of the scientific community for his lack of rigor and standards. (“My body is a crash-test dummy,” he later wrote.)

He remained at Penn after his degree, studying psychoanalysis under Robert Waelder, who had studied with Anna Freud in Vienna. But he was ultimately more drawn to biophysics, which offered “more satisfying” concepts to explain the brain’s mysteries. He joined the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and began a decade of experiments on the brain, “becoming absorbed in the pursuit of the conscious self hidden somewhere in those cerebral folds.”

At the time, neurophysiology was puzzling through a question: does the brain need external stimulation to remain conscious? Lilly built the world’s first isolation tank to find out. And true to form, he was the first test subject.

He’d soon learn that no, the brain didn’t go unconscious when devoid of sensory input; it tripped balls.

By reducing external stimuli to nil, Lilly and his colleagues found that the sensory deprivation tank could produce all manner of altered states, from waking dreams to out-of-body experiences to alternate realities. The tank was lightproof and soundproof, with saltwater kept between 93 to 94 degrees Fahrenheit. (“So you can’t tell where the water ends and your body begins,” Lilly said).

Lilly found himself spending more and more time suspended in the womb-like embrace of the isolation tank over that first year. “Wouldn’t it be great to float like this 24 hours a day?” he marveled to his friend Pete Shoreliner. “You should look at dolphins,” Shoreliner said. “They’re available. Go down to the Marine Studios in Florida.”

At the time, cetacean communication research was in its infancy. Dolphins were considered vermin to East coast fishermen, who called them “herring hogs.” Lilly visited the Marine Studios and was instantly struck by the possibilities of cetacean intelligence after seeing the size of their brains.

Lilly opened a dolphin communication research lab in the Virgin Islands and began a decade of experiments. He found that dolphins could be taught to mimic the sounds of human speech. But what he wished to understand was what language the dolphins were speaking to themselves. Given their larger, more evolved brains, Lilly hypothesized that the dolphin mode of communication would be more sophisticated than ours.

He began recording their click-and-whistle conversations and discovered that dolphin frequency of speech in water matched exactly the frequency of human speech in air. Lilly concluded that the dolphins were speaking a language similar to humans, just much faster.

His research on dolphin communication and the unappreciated intelligence of cetacean life, published in Man and Dolphin (1961), captured the public’s imagination. Astronomers like Carl Sagan saw in Lilly’s efforts the foundations of approaches that could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial intelligence. NASA provided Lilly with financial backing to build another lab in the Caribbean in 1963.

But Lilly never succeeded in his quest to crack the dolphin language. Along the way, he started taking acid. And that’s when things got weird.

LSD was legal and in ample supply in the 1950s while John Lilly was at the NIMH. But he held off trying it until 1964, after almost a decade of experiences in the sensory deprivation tank. Of his first time on LSD in the isolation tank, Lilly said: “I left my body and went into infinite distances — Dimensions that are inhuman…I traveled through my brain, watching the neurons and their activities.”

Lilly started injecting the dolphins with LSD, but nothing happened. As his psychedelic use increased, his enthusiasm for carrying through experiments at the research lab waned. Friends watched Lilly go “from a scientist with a white coat to a full blown hippy.” Gregory Bateson, who was director of the lab, left the project, and by 1968 funding had dried up. Lilly would continue research into dolphin communication for the rest of his life, but with private funding and using fringe methods like telepathy.

Any benefits of the lab’s research were overshadowed in the late 1970s when Hustler published a story about one of the lab assistants and a dolphin named Peter. Because dolphins were prone to sexual urges that disrupted research, the lab assistant Margaret Lovatt would relieve Peter when such moments arose. “I wasn’t uncomfortable with it, as long as it wasn’t rough,” she recalled years later. “It would just become part of what was going on, like an itch — just get rid of it, scratch it and move on. And that’s how it seemed to work out. It wasn’t private. People could observe it.”

When reporter Judith Hooper asked scientists for John Lilly’s whereabouts in the early 1980s, most responded with something along the lines of: “Do you mean, what dimension?”

Since the early 1970s, when he started taking the psychedelic ketamine in combination with sessions in the sensory deprivation tank, Lilly’s writings and interests grew increasingly eccentric. A ketamine vision told him that humans would create a malevolent network of “solid-state systems” that would evolve into an autonomous bioform bent on destroying humanity. He said he routinely communicated with a hierarchical group of alien beings he dubbed the Earth Coincidence Control Office (E.C.C.O. —an inspiration for the 1992 video game Ecco the Dolphin). The purpose of E.C.C.O was to guide human beings away from their “destructive programming” and thereby evolve to higher levels of being.

In his final years, Lilly was seen as something of a psychedelic visionary (he was reputed to have taken more LSD and ketamine than anyone alive), and he would oftentimes receive phone calls from seekers attempting to decipher his visions about aliens and cosmic entities. Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary were known to stop by for dips in the sensory deprivation tank, as were the physicists Richard Feynman and Carl Sagan.

Lilly never found the elusive self that drove him from the research lab to the ocean depths to outer space. “Guides at each level above ours pretend to be God as long as you believe them,” he recalled. “When you finally get to know the guide, he says, ‘Well, God is really the next level up.’ God keeps retreating into infinity.”

But along the way, Lilly did develop a maxim to guide his exploration, one he could summon by memory up to his final days:

“In the province of the mind what one believes to be true, either is true or becomes true within certain limits. These limits are to be found experimentally and experientially. When so found these limits turn out to be further beliefs to be transcended. In the province of the mind there are no limits. However, in the province of the body there are definite limits not to be transcended.”

John C. Lilly’s body reached its limit on September 30, 2001, at the age of 86. As his delightfully-anachronistic website puts it:

“We can only imagine what limits he is transcending now.”