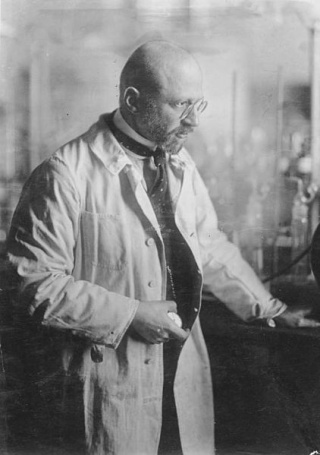

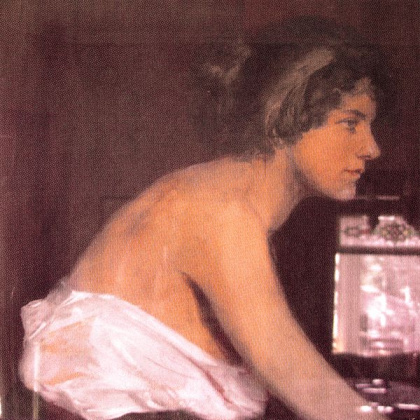

dr Clara Haber, née Immerecht (1870 – 1915)

Friedrich Ekkehard Vollbach

"Sicknesses of the soul can lead to death,

and that can become suicide."

G. Chr. Lichtenberg

My uncle, a chemistry teacher by trade, wrote a chemistry textbook in the late 1920s. In the section of text that explained the "Haber - Bosch - Process" 1, he had inserted the picture of one of the spiritual fathers of this process, the chemist Dr. Fritz Haber. That was the reason for the Nazis, this textbook, which was quite understandable and It was informative to rely on the index and to ban it. That's why I was already interested in the chemist Dr. Haber as a primary school student, who contributed to the production of artificial fertilizers and thus made effective use of the land possible.

Fritz Haber was a Jew. That was enough for them Ideologues of the so-called Third Reich in order to want to erase the memory of an important German scientist.

However, today's view of this chemist is not uncritical. The reason for this is of course not his Jewish descent, but the fact that thousands of soldiers suffocated miserably from poison gas as a result of his research and his cooperation with the military in World War I. His wife, the brilliant chemist Dr. Clara Haber, née Immerwahr, could neither accept nor mentally cope with her husband's deadly research. Maybe that's why she died.

In order to be able to trace the life of this woman, we have to go to the former Breslau: In 1875, five years after the birth of Clara Immerecht, Breslau (Polish: Wroclav) with 239,000 inhabitants is the third largest city in the German Empire. Around 6% of the inhabitants profess the Jewish religion. In 1872, this large Jewish community built a new synagogue, despite controversial theological disputes within the community, which offered space for 1,800 visitors and was one of the most magnificent in Germany.

If you consider the size of the Jewish community in and around Wroclaw, it is not at all surprising that of the nine (!) Nobel Prize winners who were born in Wroclaw or worked in Wroclaw, four had Jewish roots, namely the physician Paul Ehrlich, the chemist Fritz Haber, the physicist Otto Stern and the economist and mathematician Reinhard Selten.

The merchant David Immerecht and his wife Caroline, née Silberstein, also belonged to the Jewish community in Breslau. Her son Philipp studied chemistry in Breslau and Heidelberg. After his doctorate, he dreams of an academic career at a university, but he is realistic enough to know that as a Jew he has few chances in this regard. That is why he manages the Oswitz estate in Polkendorf (today Wojczyce), which is family-owned. Philipp Immerwahr first bred sheep there, but then switched his business to grain production. Since he is a chemist, he experiments with artificial fertilizers, achieves very good crop yields and thus achieves some prosperity.

He marries his cousin Anna, née Krohn, who is seven years his junior. The couple have a son (Paul) and three daughters (Elisabeth, Rosalie and Clara). Clara, the youngest of the three daughters, was born on June 21, 1870. (18 days later France declares war on Germany, the trigger for this was the so-called Ems dispatch).

The children grow up in a very liberal and education-oriented family. For example, the father advocated intellectual education in women, a view that by no means all men of the time shared with him. The Immerwers remained Jews and did not allow themselves to be baptized, but the family did not attend the synagogue service.

In the summer, when the family lives at Gut Oswitz, the children receive private lessons. In winter the family lives with the grandmother in Breslau. There the daughters attend the higher girls' school. The girls stayed about nine to ten years in this educational institution for the so-called higher daughters. After that, the students left school without a qualification. That wasn't necessary either, because the graduates were only supposed to be prepared for their roles as wives, housewives and mothers. You didn't need a qualification for that.

The director of the girls' school, Ms. Knittel, an educated, well-travelled woman who was close to the women's movement, supported the highly talented Clara Immerwahr. From her, the schoolgirl received the non-fiction book by the Englishwoman Jane Marcet entitled "Conservations on Chemistry", which was published in 1801. This book was probably the impetus for Clara's interest in chemistry.

The father is visibly pleased that his daughter is interested in his profession Knittel also ensures that Clara is taught chemistry by the school's chemistry teacher outside of regular classes.

In 1890 Clara's mother died of cancer. The father hands over Gut Oswitz to his daughter Elisabeth and her husband Siegfried Sachs. Father and daughter Clara move to Breslau, where the grandmother owns a large clothing store.

At this time, women who want to gain knowledge beyond what is offered at the secondary school for girls only have the perspective of attending a teacher training college. The training to become a teacher lasted three to four years. After completing their training, the young women can work as governesses (teachers for so-called higher circles). Clara follows this training path.

From 1893, women in Prussia had the opportunity to attend so-called grammar school courses after completing secondary school for girls. And three years later, women are even allowed to be guest auditors at the university. Clara, who now works as a governess, uses all the new opportunities for women to get an education. In 1996 she asks Privy Councilor Meyer, professor of experimental physics, for permission to be a guest student at the University of Breslau. The professor welcomes her with the words "I don't believe in spiritual amazons". Like many of his colleagues, he is a declared opponent of women's studies.

Clara manages to get the requested approval through her knowledge, her tenacity and her civil courage. She can be a guest student with the chemists. She is forced to overlook the bullying and hostility of the students and professors, to which she is repeatedly exposed. It also doesn't bother her that family and friends shake their heads in amazement at Clara's "Bluestocking".

Richard Abegg, a private lecturer, becomes her teacher Abitur as an "external" at a grammar school for boys. (There were no grammar schools for girls.) This entitles her to take up full-time studies at the University of Breslau.

Just one year later she passed the so-called association exam.3 Passing this association exam is now a prerequisite for acquiring a doctorate.

Two years later, Clara Immerwer did her doctorate with the thesis "Contributions to the determination of the solubility of poorly soluble salts" under Professor Abegg. After the disputation on December 22, 1900, to which a whole series of curious critics of women's studies had appeared, she received the grade "magna cum laude".

The results of their research still play a role in the construction of batteries and electric motors today.

Clara Immerwahr's doctorate is a sensation. After all, for the first time a woman in Germany has obtained a doctorate in chemistry. On December 22, 1900, the "Provinzial-Zeitung" Breslau read: "Our first female doctor. On Saturday afternoon at 12 o'clock sine tempore the doctorate of Miss Immerwahr took place in the Leopoldina auditorium of our alma mater."

(To commemorate the researcher, who was impressive due to her diligence, perseverance and knowledge, the Technical University of Berlin has been awarding the Clara - Immerwahr - Prize to promising young scientists from the field of catalysis research for several years.)

The praise of the dean of the faculty is quoted in detail in the article in the "Provinzial - Zeitung". But even at the graduation ceremony, he does not let himself be deterred from making it unmistakably clear in his speech that "women continue to fulfill their most beautiful and sacred duty "to have," namely "to be a place for the family."4 With her doctorate, Clara has achieved everything that a woman could achieve in chemistry at the time. Even as a chemist at the university, she did not get a job. The thirty-year-old can only work scientifically as an unpaid laboratory assistant at Prof. Abegg. But over time she is becoming more and more self-confident. Her dealings with colleagues, who often argue in an authoritarian and unobjective manner, are and remain collegial and elegant.

In January 1901, at a conference, she met the young chemistry professor Dr. Fritz Haber. He is a friend of her supervisor Abegg. In 1893 he converted to Christianity to get better job opportunities. This brought about a break with his father, who broke with him because of his son's baptism. Haber Junior can now (1898) become a professor at the Technical University in Karlsruhe. Clara Immerwahr converted to Christianity in 1897, probably also for pragmatic reasons.

In 1891, when Haber was doing his military service, Clara had met him before. Now, like before, he proposes to her. Clara hesitates. Clara, now 30 years old, only says yes when she has slept on it for the night. In August 1901 the two married. They intend to lead a research marriage like the Curies in Paris, but they will not succeed.

The young couple moves into a very spacious but very expensive apartment. That is why they cannot afford servants. As a result, Clara has to take care of the housework more and more.

In 1901 she was still able to work in the institute in the afternoons, i.e. proofreading manuscripts, translating specialist literature and doing other scientific support work. But little by little she disappears in the shadow of her husband.5 Fritz Haber's book on thermodynamics is published. He dedicates it to his wife without mentioning that she was scientifically involved in it.

She writes to Abegg: “But I will hardly be able to work in the laboratory again, because my days are filled with work. Maybe later, when we're millionaires and can keep servants. But even in my mind I can't do without it completely."

In 1902, after a difficult pregnancy, their son Hermann was born. Clara's comment on pregnancy and childbirth: "It's better to do ten doctoral theses instead of having to suffer like that." Clara refused her husband even on their honeymoon. When travelling, there is no longer a shared bedroom, the married couple live side by side in a cool atmosphere.

She gives presentations that do not satisfy her in any way from a scientific point of view, but give her a little pleasure because of the interest of the audience in her explanations. In the Karlsruhe Workers' Education Association, for example, she held a series of lectures on "Natural Sciences in the Household". Up to 100 people attended her lectures. She wrote to Abegg about their reaction in 1906: "The ladies are enthusiastic." And she is outraged when people think that the lecture she gave was probably written for her by her husband.

Between 1904 and 1910, Fritz Haber made his greatest invention in Karlsruhe, namely the synthesis of ammonia from hydrogen and the nitrogen in the air, for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1918. But Clara's record of this time looks different. In 1909 she wrote in a letter to Prof. Abegg: "What Fritz gained in these eight years, I lost that - and even more - and what is left of me fills me with the deepest dissatisfaction."7

Haber is a sociable guy who loves table fellowship. He is a good conversationalist and sometimes full of folly and wit. He frequently invites and accepts dinner parties, especially when the invitations are from influential people. And Haber loves representation, while his wife has little time for such things.

Clara has more and more to "take on the role of the representative, caring and, if necessary, auxiliary professor's wife."8 Her husband disregards his wife's scientific efforts. Fritz Haber is also an extremely ambitious "workaholic."9 This is how Clara writes to her supervisor ( 1909):

"The upswing that I got from it (marriage) was very short... So the main part (of dissatisfaction) is to write about Fritz's overwhelming statement for his own person in the house and in marriage, besides simply every nature , who does not perish even more ruthlessly at his own expense. And that's the case with me."10

The marriage was already completely in tatters when the Habers moved to Berlin in 1911, as Fritz Haber became the founding director of the "Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry" in Berlin-Dahlem. At the same time, he was appointed full professor of physical chemistry at the University of Berlin. Incidentally, he likes to teach and his students report that he was a good and interesting teacher.

The family now lives in a handsome service villa in the vicinity of the institute. But Clara, more and more in her own way, begins to oppose the role of servant wife that has been imposed on her. She is interested in the "life-reformist world of thought"11, in which ways to an alternative life are sought in a variety of diffuse ways. This is particularly evident in her appearance. She now wears reform clothes, which most of her contemporaries regard as sloppy , since the corset that "shapes" the figure is not used with this type of clothing. The reform dresses hung formlessly and loosely from the shoulders.12 (This fashion prompted the singer and comedian Otto Reutter to write the couplet joke "Helene im Reformdress".)

Her reform clothes did not correspond at all to her husband's taste in fashion, and certainly not to that of his colleagues and even less to the taste of their wives.

As time goes by, clothing becomes less and less important to Clara. The physicist and Nobel Prize winner (1926) James Franck, one of Haber's employees when using poison gas at the front, embarrassingly confused Professor Haber's wife with their cleaning lady when they met him. However, Franck quickly realized that Dr. Haber's "exaggeratedly simple clothing" was an expression of protest against her husband.13

The ladies of society can hardly believe it and are shocked that Privy Councilor Dr. Haber drinks coffee with her maids. And she also goes to the market to shop herself. The guests invited to the evening party at the Haber house are completely perplexed when they are received by the host's wife, wearing her kitchen apron. And the guests of the evening are also speechless when the lady of the house suddenly gets up in a happy group and apologizes and says goodbye with the words: she is tired now and has to go to bed because she is forced to leave tomorrow morning at 6. 00 a.m. to get up.14

Contemporary witnesses attest to the Dr. Clara Haber a great simplicity, an excessive thrift and an exaggerated conscientiousness. The latter expressed itself, for example, in the constant concern for the health of her family. Of course, her son Hermann is a bit ailing, but she exaggerates the hygienic measures to such an extent that everyone scoffs at it.15

When her husband, fascinated by a problem, doesn't come home for lunch, she brings him the food to the institute. While she means well, it always upsets him greatly because he's about to investigate an extremely complicated problem. That's why he wants to be left alone for now and not be bothered by such trivial things as lunch. Fritz Haber was rarely at home because he travels a lot. Of course he has affairs with other women.

In 1914, right at the beginning of the war, Privy Councilor Dr. Fritz Haber as a war volunteer. Clara does not share her husband's enthusiasm for war and that of her contemporaries. She sympathized with the peace movement and admired the pacifist Bertha von Suttner.16

The privy councilor and successful chemist was of course not assigned to the front as a soldier, but to the "Main Defense Materials Department". A short time later he headed the "Central Office for Questions of Chemistry" of the army . When the Chief of the General Staff in December 1914 asked the army chemists to look for a substance that would render people unable to fight, Friz Haber recommended using chlorine gas for this purpose.17

In January 1915, Clara traveled to Cologne with her husband. Soldiers and volunteers (especially high school graduates) are trained there for gas warfare. The situation at the front was recreated on the training ground with trenches containing animals. After the poison gas has been able to escape from the corresponding bottles, it spreads over the training area as a cloud of poison. The animals in the ditches die miserably. Clara is shocked. It is said that in front of the chemists present, the representatives of industry and the military, she vehemently opposed what her husband was doing. She accuses him of his work being a "perversion of science". He replies that her idealism is unrealistic.

In articles that no newspaper publishes, Clara opposes the use of poison gas. In an argument about the war and the use of poison gas, Fritz Haber is said to have insulted his wife as a traitor to the fatherland.

Fritz Haber goes to the front to oversee the preparations for the gas attack in the 2nd Battle of Ypres himself. On April 22, 1915 at 6:00 p.m., 160 tons of chlorine gas are released from 6,000 bottles. A gas cloud 6 km wide and 1 km long drifts towards the enemy positions. The effect is devastating.

Fritz Haber was promoted to captain by order of the Kaiser because of his achievements in gas warfare. He has finally received an officer's commission, which he had been denied 26 years earlier. Returning to Berlin, he gives an evening party in his house on the occasion of his appointment as captain.

When the guests had gone, he went to bed, not without taking a strong sleeping pill, as was his wont. His wife, on the other hand, writes farewell letters. Then she pulls the captain's service pistol out of the holster, goes into the garden and fires a test shot in the meadow. Then she shoots herself in the heart. Clara Immerweil died some time after the fatal shot. Her 12-year-old son Hermann is the only one who heard the shot. It is he who wakes up the father.

One day later Fritz Haber travels to the Eastern Front - as ordered - which he should not have done in such a case. He leaves his son alone in Berlin.

Instead of the usual obituary notice, the Grunewald newspaper read on May 8th (!) 1915: “The wife of the Privy Councilor Dr. Haber in Dahlem, who is currently in the field. The reasons for the unfortunate woman's actions are unknown."

Clara's remains are cremated, suggesting that she and her husband were freethinkers.

The real reasons for Clara's suicide are not clear, because the last months of Clara's life consist of more gaps than facts that can be verified by reliable sources.

The family has always kept quiet about it. Fritz Haber only commented on his wife's suicide once, namely in a letter from June 1915, in which he wrote: "She couldn't bear life any longer." Section report is not available.The farewell letters cannot be found, although the service personnel claim to have seen them.

Information clarifying the motive for the crime is not known. All information on the unfortunate woman's death has been withheld or destroyed. However, this corresponds to the then usual practice in the so-called better circles. One can only try to reconstruct the life of Clara Immerwere with the scant material available.18 This has also happened to a large extent recently in the media (up to the television film entitled "Clara Immerwere", which was released on May 28th was broadcast on ARD in 2014).

Haber's comment about Clara's death in the letter of June 1915, the family's insinuations and the fact that we know of Clara's three stays in a sanatorium (1906, 1910, 1913) led to the assumption that Clara was mentally ill and significantly hereditary in this regard. The suicide of her son Hermann in the USA in 1947 should confirm this assumption.

Some biographers see Clara Immerwahr as a tireless peace activist who works vehemently to ensure that chemical science is not perverted by the production of weapons of mass destruction. In order to rouse the public to stop the inhumane use of poison gas that her husband helped develop, she shoots herself with her husband's service pistol, a suicide that is rare for women.

For other biographers, Clara is seen as the victim of her egocentric husband, who macho-style forces his wife to play the role of servant housewife and doesn't allow her the possibility of an academic career. Then there are his affairs, which humiliate Clara, and his ambition and workaholism, which know no bounds. Life next to this man is becoming increasingly unbearable for Clara.

Which thesis is the correct one?

The letter of condolence from the former headmaster to Hermann Haber on the occasion of Fritz Haber's death in 1934 reads:

I am thinking of "how your mother came to me immediately after receiving a telegraphic message telling me about the success of the first gas attack" ( of the one near Ypres)."19

And the institute mechanic Hermann Lütge, who greatly admired the Habers, writes in his memoirs of the Habers: the wife of the privy councilor was "simply not (was) in a position to think intensively about the reprehensibility of gas warfare. The boss may have been proud of her husband's achievement." 20 These written testimonies do not fit at all with the image of the chemist who courageously fought against the gas war.

Lütge wrote down his memories of the events of 1915 in 1934. In the meantime 40 years had passed. He refers to statements (which can no longer be verified today) by the servants in the Haber house and by the chauffeur. Lütge's dramatic and imaginative details are welcomed by some biographers, especially when it comes to reconstructing the last hours of Clara's life. These details include the report from the evening party at which Haber's appointment as captain was celebrated, Lütge's announcement that Charlotte Nathan (Haber married her two years later) was also present that evening, and Clara in shameful togetherness with her husband was surprised. Lütge also only knows about the farewell letters, the murder weapon and the two shots fired.

The ultimate and true cause of the tragic death of chemist Dr. Clara Haber, née Immerwere, will probably remain in the dark.

footnotes

1 Process for the synthesis of ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen and hydrogen

2 Derogatory term for educated women who do not correspond to the usual "ideal of femininity". Today they would probably be called emancipates.

3 To date, there have been no state final examinations for chemists, neither at universities nor at technical colleges. Each educational institution determined for itself what knowledge a graduate must have. Consequently, there were considerable differences in the level of applicants for a position as a chemist in industry. Industry representatives demanded a comparable final exam for chemistry students. For this reason, the association exam was introduced in 1898, which now had to be taken at both universities and technical colleges.

4 Quoted by V. Ullrich, The Destruction of a Woman, ZEIT ONLINE, 1993

5 Gudrun KIammasch, The conflict between Clara Immerwahr and Fritz Haber, lecture in the General Studies at the University of Heidelberg on June 2, 2014

6 Margit Szöllösi - Janze, Fritz Haber - a biography, CH Beck, Munich, 1998, p. 398

7 quoted by H. Heher, Who is Clara Immertrue? 1992

8 Luise F. Pusch, Clara Immerwahr, married. Haber, biography at Fembio (www fembio org)

9 Jewish Women's Archive (jwa.org / encyclopedias / article / immerwahr - clara

10 Sit. n. J. Heher, aa O.

11 Margit Szöllösi - Janze, aa O., S.194

12 The most important piece of clothing for women in the 19th century was the corset, as it shaped the women's body according to the ideal of beauty of the time (slender waist - ideal size 46 cm - prominent breasts). The average weight of a woman's undergarments alone was 5 pounds.

13 Margit Szöllösi, aa O

14 ibid., p. 195

15 ibid

16 Erwin Starke, The Chemical Disaster (The Death of Clara Immerecht, Tagesspiegel, April 2015

17 Jörn Heher, aa O.

18 Gerit von Leitner, The Case of Clara Immerwahr: Life for a humane science, CH Beck, Munich, 1994

19 M. Szöllösi - Janze, a. a. O., S.397

20 a. a. O.