The stage crew’s view of 500,000 at Woodstock in Bethel, NY. All Photos from the Chip Monck Archives, courtesy Henry Diltz

This month celebrates the 53rd anniversary of The Woodstock Music & Art Fair, which burned its place in history Aug. 15-18, 1969. Festivals were somewhat in their infancy back then. Woodstock would make history as the festival of all festivals and would define a culture as no other festival had done.

One of Wavy Gravy’s stage announcements: “There is always a little bit of heaven, even in a disaster area” rings true for Lighting Designer Chip Monck. “Woodstock was a production disaster,” Monck says. He’s qualified to make that assessment. And then he takes off the rose-colored glasses and takes a trip back, telling the story of how one of the most legendary stages—measuring just 80’ x 100’—that served as a platform for the Voice of the Woodstock Generation, was essentially a failure. But it all worked out well in the end.

Monck was not new to lighting when he got the gig. By age 16 he got his first lighting gig at Altman Stage Lighting and by 20, he was prepping the first Newport Folk Festival. At age 24 he established the Chip Stage Lighting Corp. After stints lighting The Doors, The Byrds, The Rolling Stones and more, he was the lighting designer and stage manager for The Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. That year he started working with legendary concert promoter Bill Graham, and The Fillmore East became Monck’s second home.

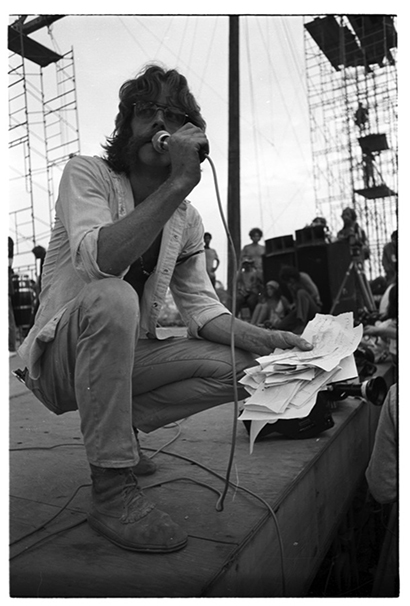

Chip Monck’s stage announcements, warning of weather and brown acid, became immortalized.

‘Brown acid going around…’

When the buzz swarmed around about the planning of the Woodstock Festival, Monck got word through the William Morris Agency that “Michael Lang was booking everything in Christendom for the festival,” Monck says. He met with Lang—who was one of the four who formed Woodstock Ventures to produce the festival—and Monck emerged with job titles as the festival’s production designer, production manager, lighting designer and operator.

But his most recognizable role was not just lighting the stage but being on the stage as the Master of Ceremonies, whose legendary speech “there’s some brown acid going around that’s not particularly too good” was immortalized along with other stage announcements in the documentary film and on the soundtrack album. This emcee role was a last-minute decision from Lang, who looked out on the sea of humanity waiting for the fest to start, realized he had no one to introduce the artists, tapped Monck on the shoulder and said, “We need a little help. We’ve forgotten to hire an MC, so you’re it.” Monck was glad he didn’t have advance notice of his role as the human public address system over the next few days, as he didn’t have time to get nervous thinking about it. He was called The Voice of Woodstock for his memorable announcements, but in between, he still had a lighting gig to do. And that presented its own last-minute challenges.

The 80’ x 100’ wooden stage hosted Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Santana, Jefferson Airplane, CSN&Y and more.

‘The Weight’

Monck’s original stage design was customized for the festival’s first proposed site in Wallkill, NY, but as permits and townspeople weren’t approving the onslaught of hippie festivalgoers, the new site was set for Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm in Bethel, NY. It was just three weeks away from opening day. A different roof was constructed for the stage.

“My major Woodstock error was voting for the wrong stage design,” Monck recalls. “The moment I saw the wooden truss lumber arriving, I knew my goose was cooked. The load bearing assessment of the roof—the massive timbers were probably a visual display of strength, but they were of such weight, there was no additional load bearing capacity of the two support poles. And because of the shortening of one of the two poles, in their unloading and reducing the other to match the roof trim, its elevation for lighting was unfortunately far too low.”

He adds, “The design was neat, looked great, but in execution, it never did what it was supposed to do. The greatest disappointment was to end up with a roof that was not load bearing. Big mistake.”

He knew that the roof could not hold up his 650 specified lighting units. “The old fat Kliegl 2kW ellipsoidals were heavy, but a rough count of the 650 units at around 20 lbs. each equals 13,000 lbs. And that’s without the cable, distribution and rigging, which I’d venture to say that was another 3,000 lbs.” There was nothing else to do but stash the 650 fixtures below the stage, he says, where they rusted in the rain. Meanwhile, Monck had pulled his lighting crew from the Fillmore East in New York and found that their work ethic had much to be desired. “It only got tough when they didn’t like [to work] dusk ‘til dawn,” he notes of the 24-hour cycle they were on. This meant he had to train a crew of newbies during the event—under the deck between act intros—showing them the basics in lighting. Of utmost importance was instructing them on how to keep the Strong Super Trouper followspots lit.

“The Strong Super Trouper used a high-intensity carbon arc light source, two pencil-thin copper clad carbon rods that are motor fed together, point to point,” the LD explains. “That, at its highest intensity, gives you 41 minutes of light, and then you replace the carbon rods.”

Monck used 12 Super Trouper followspots rigged on four towers located at 100’ distances from the stage. The followspot operators had to climb up on the top of the 60’ high lighting towers to run the lights. “It was difficult to come up with special looks with only 12 lamps to light a feature film,” he admits. This is why selecting the locations for the towers was so critical in the early construction of the stage. “I was comfortable with the towers at 100’ throws. The reason the length of throw is important is that the lamp is worthless at a farther distance.”

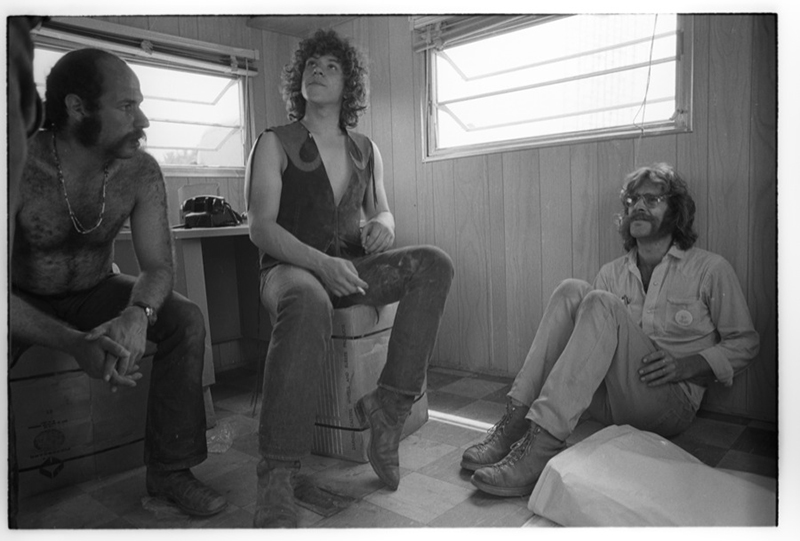

Woodstock Co-Founder Michael Lang and Lighting Designer Chip Monck on site during construction of the stage and spot towers.

‘Rainbows All Over Your Blues’

While Monck was supposed to light the artists not only for the crowds, but for the cameras, he said there were no directives given. “Performance lighting was my interest,” he says. For film continuity, he used just backlight/kickers and some sidelight, which worked for him at Monterey Pop, which was also filmed. “Woodstock’s eight front lamps were my paint brushes,” he adds, explaining that the way he used the iris, size, color and intensity were the ways he made a personal statement about the importance of the artist, at that moment. “I use saturate color, I need punch and intensity, often two color gel frames together—using #1 amber and #2 lavender—for a more notable skin tone.”

His limited lighting rig didn’t limit his artistic creativity, however. Janis Joplin was one of his favorite artists to light for the cameras. Hitting the stage at 2 a.m. Sunday, Monck managed to display a rainbow effect on the blues artist, with yellow specifically highlighting her face and her body below glowing in red. “It was a test,” he admits about the lighting situation, “but it was so rewarding.” Her performance was not included in the original film and soundtrack releases, but can be seen and heard in later compilations.

While Monck made do with lighting, communicating with the operators on the towers was another matter. The intercoms for the production team were causing trouble. “The only thing that’s more important in one’s toolbox, other than AC/power, is one’s intercom,” Monck notes. “There was a problem with intercom clarity at the site. You must understand, the headsets were telco operator sets in one ear, and not noise cancelling. When the rain came, we were barely able to communicate.”

And that rain, mixed with the mud—combined with the audience pressure on the field of moist soil—acted much like cement. After the event cleared out, the cables and intercom cables wouldn’t budge—even by deploying the Caterpillar D9 bulldozer—and Monck claims they still lie buried underneath the farmer’s famous field.

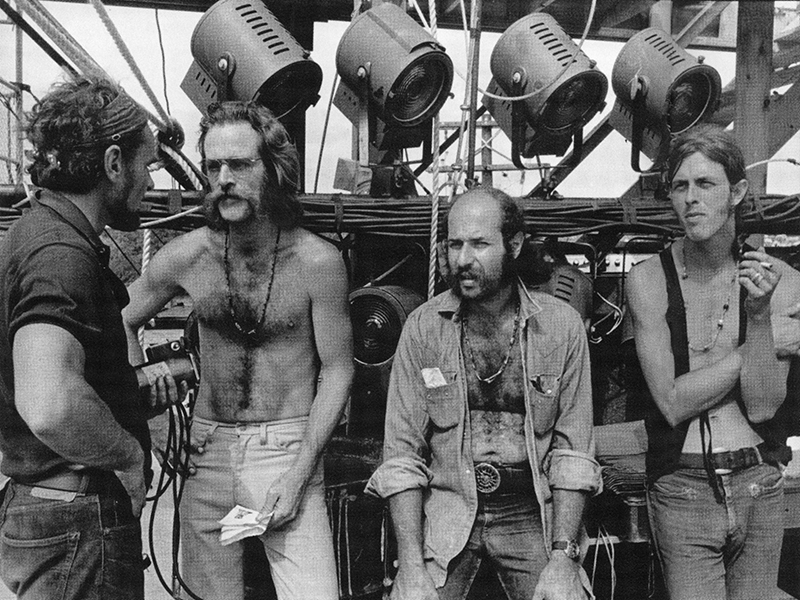

Chip Monck, second from left, trains his lighting team.

‘Turn, Turn, Turn’

Meanwhile, Monck says another great stage idea—the turntables— was “a failure that actually turned out to be a blessing.” The stage turntables were going to allow all the acts to switch in and out of their performances more quickly. Steve Cohen [Not to be confused with LD Steve Cohen, longtime designer for Billy Joel] was building the turntables on the stage deck below.

“There were six half-round segments in a plus/minus 36-40’ diameter,” Monck describes. “The unloaded half sections were upstage of the performances. All the guests and acts, anyone in the area, simply stood on the 18” high sections for a better view, overloading the 2×6 wooden caster supports, and the turntables collapsed.”

The wood might have held if there had been stage security to prevent the heavy gathering on it, he explains, and then the wooden substructure would have been sufficient, and the collapse would not have happened. Although he still believes that the turntable construction was a failure from the start. “The turntables’ failure was simply that the sub-structure below the half circles should have been steel.”

And why did its failure turn into a benefit? Because of the traffic jams blocking inroads into the festival, many of the artists could not physically get in, with many choppered in late a few at a time by helicopter. “Had the turntables worked as planned, we would have used up all the acts available for that day by midnight,” Monck reveals. “With the next acts not scheduled until 8 a.m. the following day, the 24-hour music cycle [that it turned in to] with lengthy changeovers was an absolute necessity.” After all, they were looking out past the stage to the undulating sea of 500,000 people who needed to be entertained.

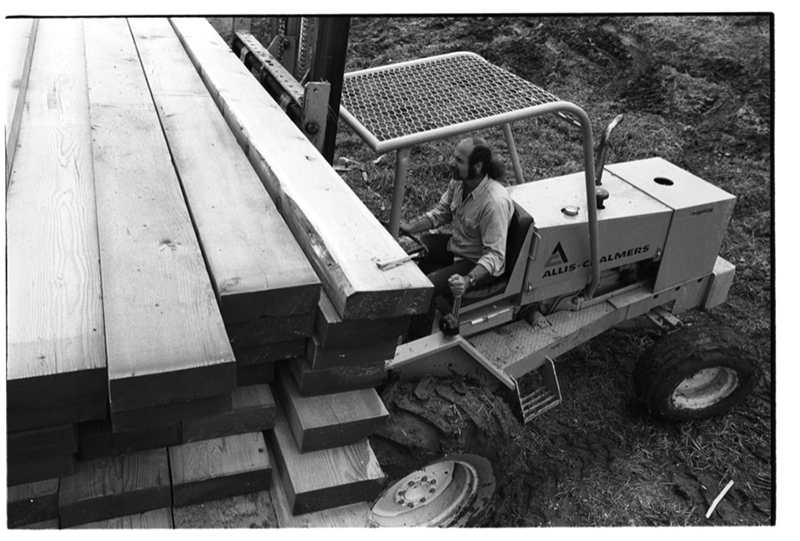

Steve Cohen is busy building the stage turntables.

‘Carry On’

So, while Monck dubs the production element a “disaster,” he lauds the resulting film as a “triumph,” and that is how most people nowadays know of Woodstock. Directed by Michael Wadleigh, Woodstock won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1970. One of the editors was a young Martin Scorsese. “Marty [Scorsese] cut his chops there, and the split screen was the only way to use the 17 miles of film, half of which was left on the cutting floor,” the LD says.

Chris Langhart, technical director and designer, was “an absolute necessity” in anything from design to structural analysis, Monck adds. “He basically kept the majority of systems alive at Woodstock: water, electrical distribution, followspot issues, the telephone system. He built the Over Road Bridge, behind the stage, the equipment elevator, the light show bridge. And he knew we were f’d with the incorrect choice of stage design, which could only just support itself. Should have listened!”

Monck was honored with the 2004 Parnelli Lifetime Achievement Award for his lifelong work in the industry—which never stopped after Woodstock. And he still loves the old technology. “I don’t use moving lights at all, and I still suffer from the loss of the PAR 64!” But from his Australia home base, he is currently working under an NDA on a projected touring design that is filled with moving lights in the rig. So, he will have to make a go of it.

The Voice of Woodstock looks back fondly, with loads more stories to retrieve and revel in from his memory bank. “To make a thumbnail sketch of the months of planning and movement is not possible,” he reflects. “The spirit, the support, the selfless gifts, the energy and the care for others that blossomed in the mud was something to behold. Everyone walked away with something of value.”

Steve Cohen, Michael Lang and Chip Monck have a meeting of the minds.